Syltenberget, Norrköping, Sweden.

Project Partners

Peter Lynch, architect and project director. Researcher, KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm.

Martin Heidesjö, urban planner, Norrköping municipality.

Dr. Mats Nordahl, data scientist, Division of Theoretical Computer Science, KTH Stockholm.

Anna Asplind, dancer/choreographer.

Project Consultants

Peter Korn, garden designer and plant specialist.

Linnea Andersdotter Rundgren, ecosystem restoration designer. Vice chair of Biotopbyggerna.

Project Overview

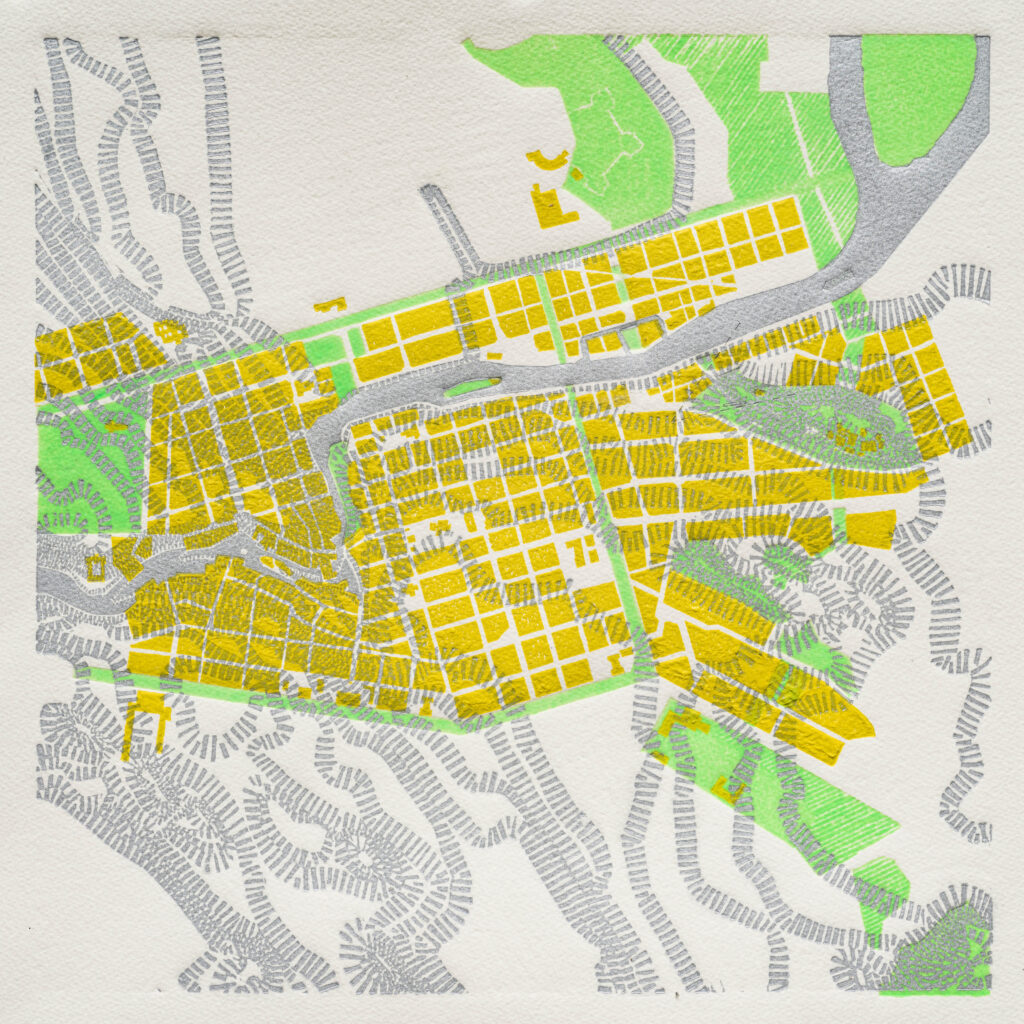

Timescape Garden is a biodiversity micropark on Norrköping’s Syltenberget, a forested hill near the city center. The site is directly south of the Motala river, surrounded by industry. In a few decades industrial uses will be replaced by high-density residential and commercial development. The garden is a testbed for new methods of site analysis and biodiversity monitoring.

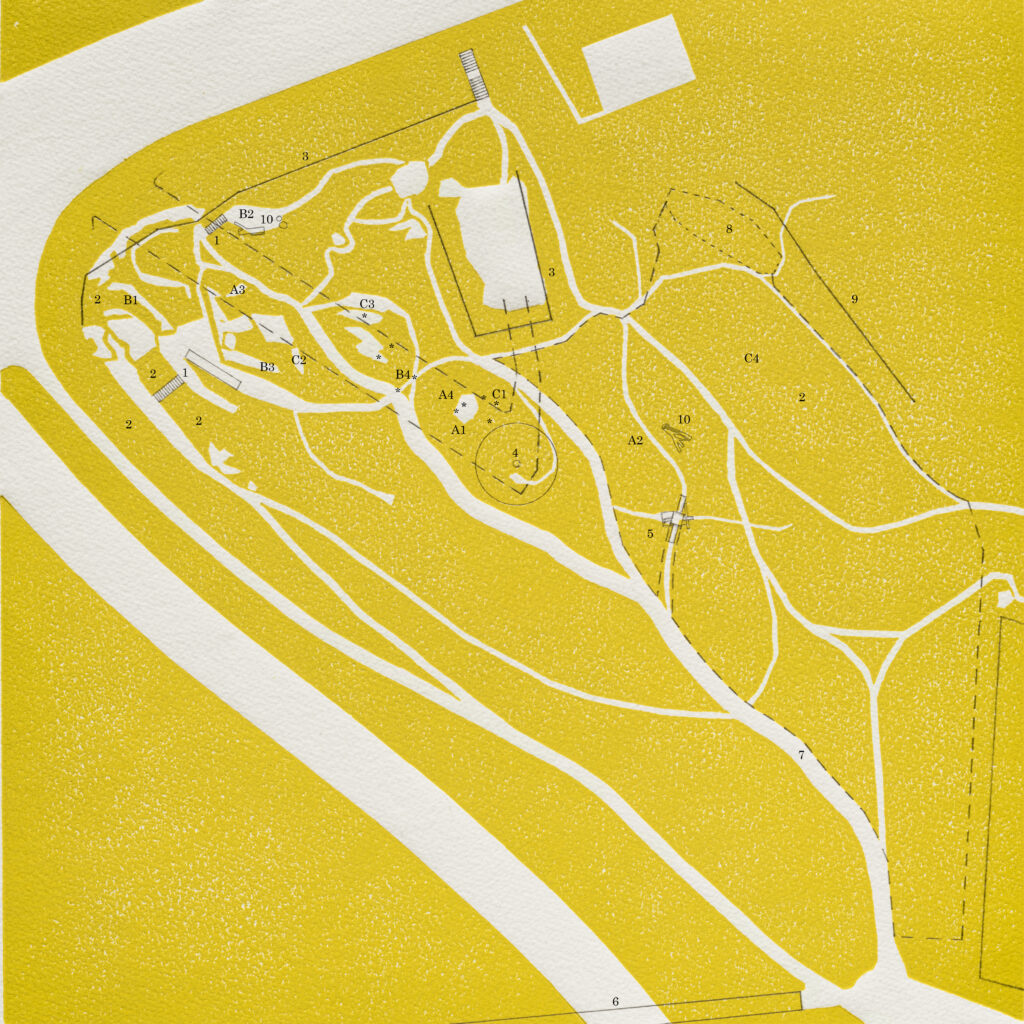

Human beings and animals follow paths because they wish to go somewhere and do something. Their desires are expressed in their movements. This project analyzed the movement of people and animals in a particular place, the western end of Syltenberget ridge, Norrköping, using different techniques and methods. The goal was to improve our ability to design urban wild gardens in a way that benefits both the human and the non-human world. Specifically, the project sought to improve knowledge about design for biodiversity, develop methods of biodiversity monitoring, and test landscape design approaches that have the potential to heighten visitor’s attunement to the natural world.

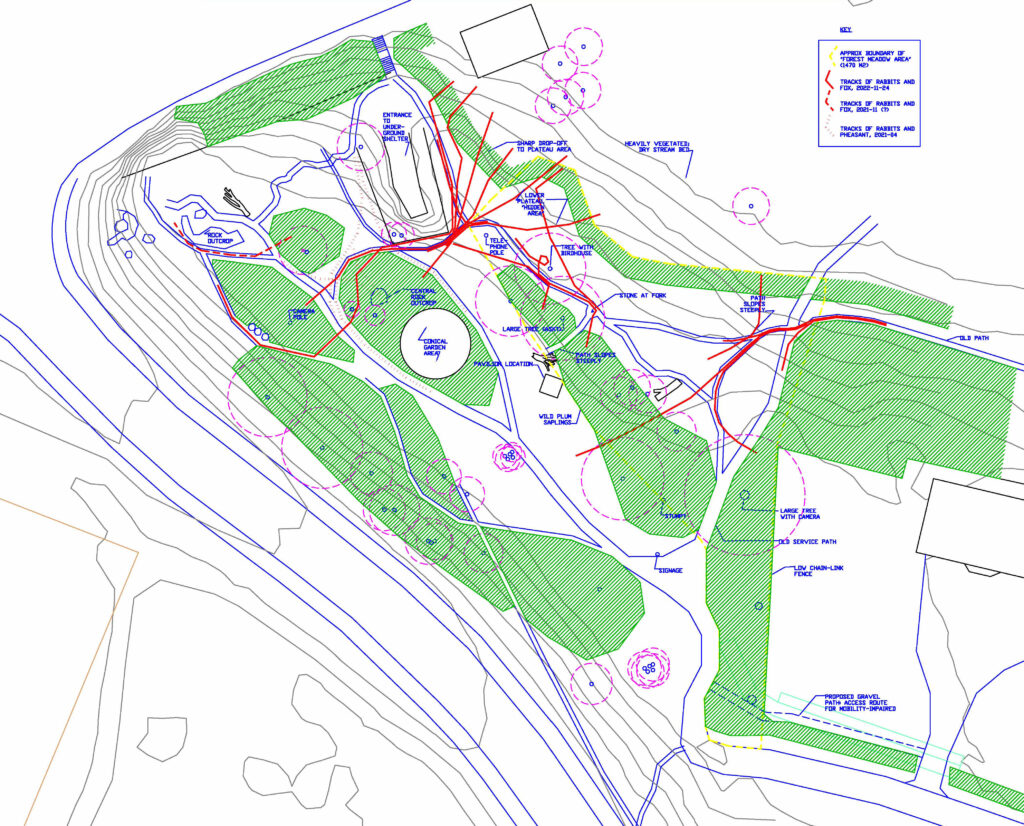

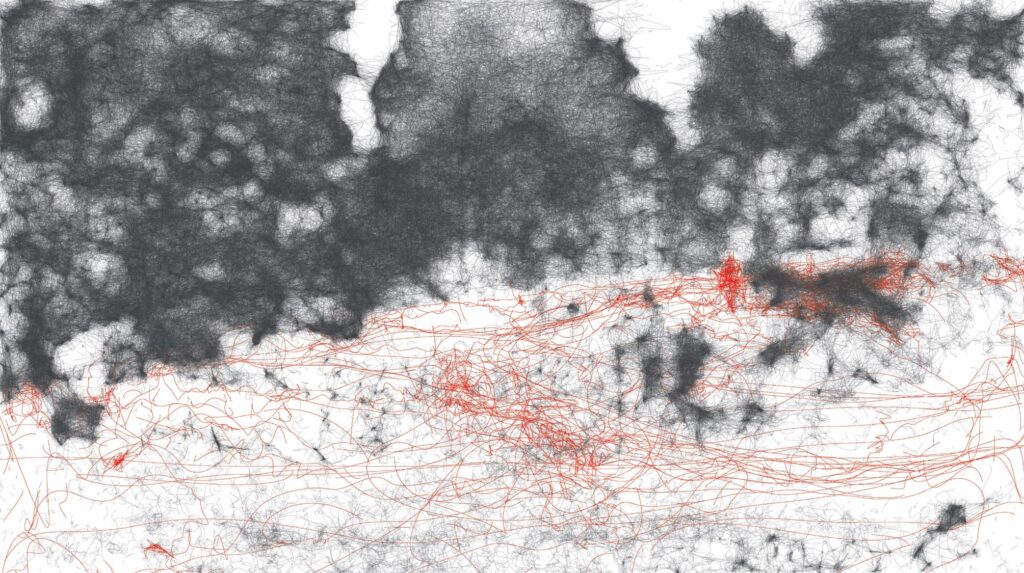

For more than three years– spanning the time before and after the planting of a wildflower garden and an edible forest glade– three video cameras have been continuously recording the project site. The raw video footage is processed by an anomaly detection program, which isolates video clips that contain atypical movement data. Paths of moving objects within the field of view are converted into vector lines. The movement of every object in the study area is traced to a high degree of precision: even the trembling of a leaf or blade of grass is registered. An AI-based motion analysis program sorts these lines into different categories–movements of birds, insects, and land animals; movements of pedestrians; and background noise (vehicle traffic, motion of grass and leaves). These lines can then be sorted further, by their apparent speed and direction. When the system is developed further, it will also be possible to sort lines by their geometric characteristics. In this way, the presence of different animal taxa can be sensed. For example, birds of different species can be identified by their characteristic flight paths: their way of darting, swooping, soaring…

The initial design for the project was part of a group exhibition created and curated by architect Yael Hameiri Sainsaux entitled “Conceiving the Plan: Nuance and Intimacy in the Construction of Civic Space. In Honor of Diane Lewis (b. 1951 – d. May 2, 2017)” at the Italian Pavilion of the 17th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, October 8 – November 21, 2021. It was also exhibited at Cooper Union, New York City in April 2022, and is featured in Conceiving the Plan: Nuance and Intimacy in Civic Space, a large-format book of essays and projects honoring Architect Diane Lewis, published in April 2022 by Skira Editore.

Research Dimension

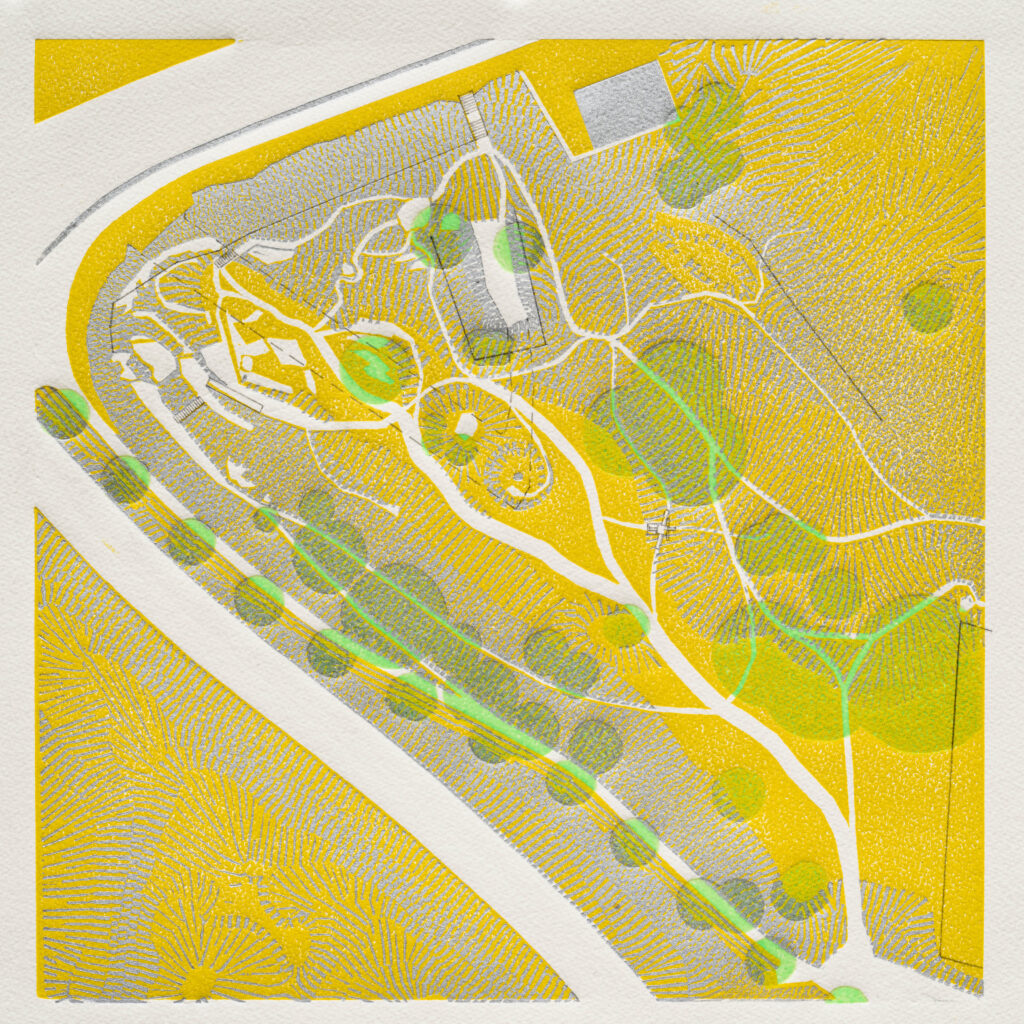

Vinnova, Sweden’s Innovation Agency, awarded the project a research grant from October 2021- September 2024. Data collection at the site had already been underway for one year. The School of Architecture at KTH Royal Institute of Technology (Stockholm) and Norrköping municipality were grant partners. The first part of the project, a 3000 m2 wildflower garden at Syltenberget, was realized in May 2022 with support from Vinnova; in-kind support from Norrköping Municipality; private sponsorship; and volunteer help from members of Naturskyddsföreningen Norrköping. World-famous plant specialist Peter Korn prepared the planting plan, supplied plant material from his nursery, and directed the planting work. In addition to the wildflower garden area, the Timescape Garden encompasses a forest glade. In 2023 Norrköping municipality staff led by Linnea Rundgren, ecosystem restoration designer, transformed the glade, adding over 40 new plant species to increase food supply for birds and ground animals. The area of the Timescape Garden now totals 6000 m2.

- The project applied dance-based methods of site analysis developed by Swedish dancer/choreographer Anna Asplind, who draws inspiration from the 1960’s work of dancer Anna Halprin and landscape architect Lawrence Halprin. At the Timescape Garden Asplind used dance-based methods to identify key paths, locations, viewsheds, and positions of the body within the site.

- The project tested a video-based approach to rhythmanalysis–a method of site analysis invented by sociologist Henri Lefebvre in the 1990’s. He proposed that designers and sociologists should observe and describe rhythms and patterns unfolding over time, in order to understand the character of a place. Lefebvre’s method of observation, sitting and watching a place or landscape from a half-hidden position for a few weeks, has obvious limits: a person cannot observe a place over the entire cycle of one day, let alone the cycle of a year. Some events, for example the presence of certain animals, are sporadic and unpredictable; one needs a longer time-frame to witness them. In the animal world, many activities take place under cover of darkness. As a supplement to Lefebvre’s method, researchers gathered and studied 4K video footage of the Timescape Garden. Three cameras continuously recorded the project site from different positions and distances over a three year period. Cameras had infrared detectors and could film at night. Researchers used an anomaly-detection algorithm to edit down the raw video data (more than 40 TB) and identify video clips that might contain useful or important movement data. Watching these clips, researchers were able to recognize characteristic movement patterns of human beings and animals, and identify patterns that changed over the course of the three years. Without this pre-selection, the task of reviewing the massive data set would have been impossible.

- The project tested a new approach to biosurveying. KTH data scientist Dr. Mats Nordahl has developed an AI-based algorithm that follows moving objects within a video camera’s field of view and traces their movements with precise vector lines. The attributes of the lines–their geometry, apparent speed, time stamp, and so on– are characteristic of the objects that traced them. Nordahl used machine learning to analyze and sort vector lines generated from video footage of the Timescape Garden. The AI-based approach is able to determine, to a high degree of accuracy, which lines are traces of animal activity (the flight of a bird or insect, for example, or the path of a ground animal) and which are traces of human activity or background noise (vehicle traffic, movement of leaves and grass). The resulting data is anonymized and therefore does not conflict with privacy rights. Vector data is also much easier to store and analyze than pixel data. When the system is further developed it should be able to sort the movement tracings more precisely, according to their geometric properties. The goal is to develop an inexpensive, near-real-time method of insect, bird, and ground animal identification that can be employed in biodiversity monitoring stations. The motion-analysis-based approach could complement existing methods, which employ image-matching algorithms.

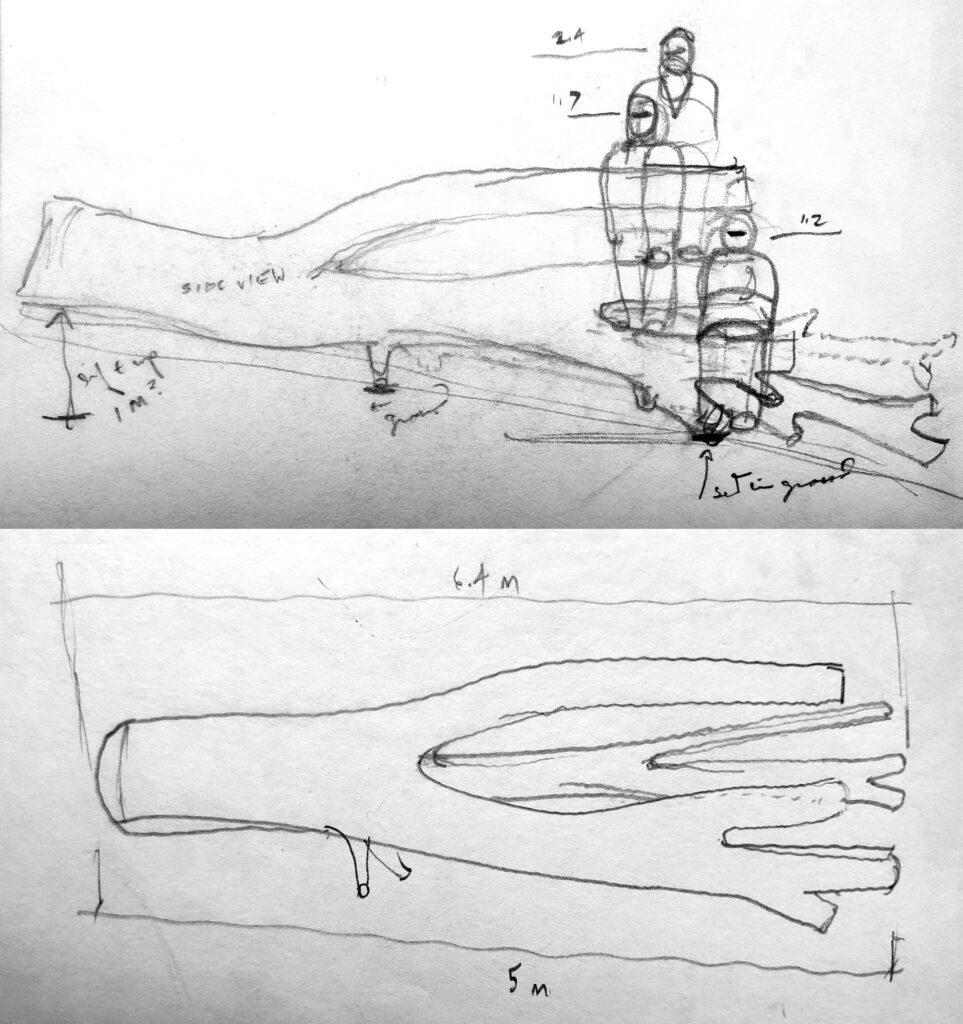

- Philosopher Barbara Adam proposes that sensitivity towards unfamiliar rhythms and tempos (“timescapes”) is a prerequisite for ecological awareness. In this project, researchers speculated that a person’s capacity to enter into unfamiliar senses of time—and therefore their ability to potentially see the world from an ecological perspective—may be affected by the position and orientation of their bodies. Standing is potentially a more reflective and attentive posture than walking; sitting more reflective than standing, and sitting back more than sitting straight. Further, the project speculated that the amount of time that a person spends in one place, looking out without engaging in physical or social activity, could be an indicator of a change in their time-experience. To explore this hypothesis, researchers placed branch-shaped benches throughout the garden that provided places for visitors to lie or sit, facing certain directions that corresponded to key places and view angles within the garden. Video documentation revealed how these benches were used by visitors. Because few visitors actually used the branch benches, data was too limited to draw a conclusion. To overcome the problem, a more inviting and familiar-looking bench was constructed within a viewing pavilion at a key point within the Timescape Garden. The pavilion has four circular openings that frame selected views. Video data will show how visitors use the pavilion.

Image credit: Anna Asplind, Peter Lynch, 2021

To listen to a conversation between Peter Lynch and filmmaker Ingrid Rieser about the timescape garden, architecture practice, and landscape architecture, visit her “Forest of Thought” podcast at https://anchor.fm/forestofthought/episodes/13–The-architect-and-the-garden–PETER-LYNCH-e12tciv

Viewing Pavilion

In September 2024 Norrköping municipality installed an open-air viewing pavilion in the Timescape Garden. The pavilion is located at the boundary between the wildflower garden and the forest glade area. The construction of the pavilion tests various details for prefabricated panelized construction, including methods to integrate roundwood posts into regular timber framing. More info about the Viewing Pavilion here